- Home

- Christine Morgan

The Eye of Mammut

The Eye of Mammut Read online

The Eye of Mammut

by Christine Morgan

https://christine-morgan.com/

https://facebook.com/ChristineMorganAuthor

Copyright 2012 by Christine Morgan. All Rights Reserved.

Cover art by Natalia Lukiyanova and Tim Morgan. Copyright 2012. Used with permission.

The Eye of Mammut

A woman drew near. He knew it by her thoughts.

Aruk paused, hands greened with juice from the shredded leaves. Then he added the fragments to the leather pot's bubbling contents. A strong but pleasing tangy scent rose on tendrils of steam.

The woman's presence burned brighter, a flame in his mind. She was worried. Conflicted. Torn. She wanted his advice, but was afraid.

He shrugged. She would come, or she wouldn't. They usually did, once they'd gathered their courage.

He went to the back of the cave and rummaged through the many baskets of food that were stacked alongside cured furs, un-knapped flint, sections of bone and antler, spears and tools. The stores were far more than any lone man had use for. But they always brought him something in gift, and he would never insult them by refusing. If winter came on harshly, he could always offer back to the tribe.

When he had selected a few hunks of dried meat to add to the pot, he returned to the firepit. The woman yet lingered, gathering her courage. In her mind, the cave was an even stranger and scarier place than it actually was. The figures on the walls, traced in charcoal and ocher, loomed large and fearsome to her imaginings. As if they moved, as if they lived. The spirits of animals and warriors and mysterious forces.

Aruk hunkered upon a flattish stone between the fire and the entrance, knowing that when the woman appeared, she would see him lit from behind by the shifting flames. The bearskin he wore, its intact skull atop his head like a hood, would seem to be a part of him. The claws of the same bear, strapped to the backs of his fingers, would gleam. All most impressive, as it was meant to be.

She was approaching at last. Carefully, nervously. She was young, he sensed. Young and not yet mated, with siblings to tend but no children of her own.

He sighed, already knowing what it would likely be. This girl-woman would have her heart set on some hunter or another, but not the one to whom she'd been promised by the Old-Mothers.

He shook his shaggy head. They expected much of their Spirit-Man.

As he heard the first hesitant steps of the young woman, his hairy brows went up. This was a high-status visitor. Eldest daughter of First Woman, who was First Hunter's chosen mate.

The woman's shadow touched the cliff face. She appeared after it, arms were laden with a basket. Aruk's nostrils flared. Red-berries. His favorite. Sweet and perfectly ripe.

The lines of her body were, like the berries, sweet and perfectly ripe. Hips round, breasts full. Her dark hair was thick as moss, her eyes were wide-set and clear. No doubt, competition had been fierce for this one. No doubt, many a fine gift had been presented to the Old-Mothers in hopes of winning their judgment.

"Wise Aruk?" The woman took a tentative step into the cave.

He rose in a slow motion, raising his arms so the bearskin spread in a wide shadow against the firelight. She gasped and cringed, but held her ground. With shaking hands, she held out the basket.

"Enter," he said.

"Wise, Aruk, I am Chala, daughter of Inasa who is mate to Garu who is First Hunter of Those Who Are Protected By The Bright Eye Of Mammut -"

"Yes, yes. Sit." He took the proffered basket. His mouth watered, but he refrained. There would be time for enjoying the treat later.

Chala, in a fine wrap of reindeer skin belted at the waist with a cord adorned by many fox-tails, lowered herself to the spot he'd indicated. Around her neck, hanging from a braided thong, was a slice of smooth-polished mammoth tusk.

Aruk squatted opposite her. "You are past old enough to be mated, Chala."

She grimaced. A yellow bitterness flooded her mind, and in it was the image of a stern, muscular hunter with a bushy beard.

"You are promised to Noav," Aruk said, enjoying her startled twitch. "Second Hunter of Those Who Are Protected By The Bright Eye Of Mammut. A hunter of great status. He could provide well for a mate and her children."

Chala frowned. "He is old, and ugly, and unkind."

"I am old and ugly," Aruk said, doing his best to sound injured.

"You are the Spirit-Man," she said. "You can have no mate."

He almost rubbed at his chest, where no hunter's mark had ever been scored into his flesh, but stopped himself. "True."

"I do not want Noav," Chala said. "His last mate's children are older than me, with hearths of their own already. I said this to the Old-Mothers but they would not hear me." Her chin quivered. "Even my own mother, a woman of high status, favors Noav. She tells me I should be proud to have him."

Aruk said nothing. She squirmed under his steady scrutiny.

"I love Dyan," she said in a rush. "Dyan is good and kind and handsome. He cares for me."

"Dyan is a hunter of poor status," Aruk said.

She bristled. "The other hunters never give him a chance, and take claim for his kills. They mock him."

He nodded for her to go on.

"If he had a high-status mate, they would never dare treat him so. He needs me. Please, wise Aruk, I want Dyan for my mate. The Old-Mothers say that he would not be able to provide, that my children and I would be cold and hungry, but they are wrong. I know that they are. All Dyan needs is a chance to prove himself!"

"What would you have me do?"

"Speak to them, please," she said, raising imploring brown eyes to him. "They will listen to you."

"The Spirit-Man has no power over decisions of the Old-Mothers. They see to the needs of the tribe's life. I interpret the will of the spirits."

"It is not the will of the spirits that I mate with Noav!" she cried, making fists as if she yearned for weapons gripped in them.

"Do you speak for the spirits?" he asked.

She hung her head. "No, wise Aruk. But they must see how I love Dyan!"

"The spirits do not concern themselves with love. They gift us with good hunting, plentiful food, and new life when they are pleased. They curse us with misfortune, sickness, and storms when they are displeased."

"Am I to be cursed with misfortune, then?" Her chin had long since stopped quivering, and now thrust out stubbornly.

Aruk did not like the hue and flavor of the thoughts churning in Chala's mind. They were too smoky for him to seize, and troubling.

"Chala, do not be foolish. We cannot force the spirits to do our bidding. Would you unleash their anger on yourself? Or on the tribe?"

Her sudden wave of scorn as she arose scathed him. She had come expecting great otherworldly power. He was Aruk the mighty Spirit-Man, was he not? Instead, she only found a useless old husk. The mighty Spirit-Man was afraid of the Old-Mothers, just like all the other men of the tribe.

"It is not fair, it is wrong! You call yourself so wise. You will see. You will know better! I will have Dyan as my mate or I will have no one!"

"Chala -"

The young woman fled from Aruk's cave. Her mind was turbulence, all desperation and anger and miserable love. He heard stones click and rattle under her rapid descent. And then she was gone from the reach of all of his senses.

When next he saw her, he would remember how pretty she had been, how lively, and he would grieve.

**

Tral went from deep sleep to full wakefulness almost at once. A hunter's knack, he prided himself as he disentangled himself from his little brothers in their warmth of piled furs. Jeruf snorted, blew a spit bubble, and turned over. No one else stirred. Inasa, his mother, was

curled alongside her mate, Garu's arm draped over her swollen belly.

The cave echoed with the sounds of snoring. The fires were down to fluffy ashes and embers, shedding a wan glow. Thin pre-dawn light trickled in through its high arch of a mouth. Tral could see a dusky purple sky in which stars still twinkled, and the horizon was a band of paler blue-gold.

He tied his wrap more securely around his middle, lashed hide coverings to his feet, and picked up his spear and sling. He would bring back a nice fat bird or rabbit for Inasa and see her break into a proud, delighted smile.

As he picked his way on tiptoe toward the entrance, stepping around the fur-covered lumps of the rest of the tribe, he realized that his sister Chala was nowhere to be seen. Neither was Dyan, Tral saw as he crept out.

He sneered. Chala and Dyan. Everyone knew. Just as everyone knew it would never be allowed. Dyan! Worst hunter in the tribe. Clumsy and lazy and a liar as well.

The meadow in front of the cave sloped away into misty green, toward the dark and somnolent forest. The stillness was broken by the twitter of early-rising birds and the rustle of animals pushing through the underbrush.

Tral patted the bag of sling-stones that hung from his wrap-tie as he started for the forest. Out of habit, he glanced over his shoulder for a glimpse of the Eye of Mammut watching over the tribe's home.

He couldn't see it. Frowning, he stopped and turned around and surveyed the top arch of the opening more closely.

It should have been there. A mellow glint, like a cooling fire, catching the first light of the sun.

The Eye of Mammut … he had barely been more than a baby when it was found, but he knew the story. How Garu had slain a mammoth single-handedly, and found the Eye embedded in the earth near the fallen beast's head. Smooth like a river-stone but clear as clouded ice, honey-golden, large as a man's fist. A shape in the center, a dark line or crack that looked like a tusk when turned one way, and a spear when turned the other.

A token of good fortune, a gift from the spirits. Luck for the tribe. Luck in the hunt. That mammoth would be the first of many, bringing much meat and many ivory tusks to the tribe. A sign of blessing.

But it was gone.

Tral felt a knot in his stomach and another in his throat. He walked a few paces to one side and then the other, but the Eye still did not appear.

He remembered when Garu and Noav had scaled the sheer rock to place the Eye of Mammut over the entrance. That climb was a feat only the best and strongest hunters could have accomplished, and the others - hunters, old men, women, and children - had watched in breathless dread. But they had done it, and descended unharmed. And from that day, the Eye had guarded them.

It couldn't be gone. It just couldn't.

Thinking that it might have come loose and fallen somehow, Tral explored the meadow directly in front of the cave. He found several stones, but no Eye.

And then, tracks! Not animal prints, but the marks of hide-covered human feet indenting the dewy grass. Already, the hardy green was springing back up, obscuring the marks. They'd soon be completely gone.

The Eye … had it been taken? Had someone climbed the rocks and taken it away? The very idea was enough to make his head hurt.

Gripping his spear tightly, he followed the trail across the meadow and into the cold beneath the trees. His breath plumed up. He had a prickle on the back of his neck, and a vile taste seeping into his mouth. His skin puckered into a rash of tiny bumps.

His progress flushed a ground-dwelling bird. It exploded out of the bushes with a harsh cry. Tral jabbed wildly at it with his spear, coming nowhere close to hitting it. The bird escaped and there he stood, panting, heart thundering, body clammy with sweat.

Air slipped rapidly in and out of his flared nostrils as he grappled with his shameful scare. A bird. Him, a hunter, frightened by one bird. He was glad no one else had been with him to -

Then he caught the scents. Wolf! And blood.

His lips soundlessly formed the word. Wolf. But there was no one to hear him. Even if he shouted, would his voice reach back to the cave? Would it wake anyone? Would they find him?

Would it be in time?

His bladder seized in a cramp. He'd been too excited by the prospect of a morning hunt to think of voiding. Now it was a throbbing urgency. But nothing would draw a wolf faster than the sharp stink of urine.

Yips and snarls came from a dense thicket. High-pitched, underlain with an amused-sounding rumble. And then the sound of effortful ripping, an awful, meaty, rending noise.

Most of him was clamoring for the safety of the cave, but for some reason Tral found himself moving closer to the thicket. Holding his breath, feeling the breeze on his face and knowing he was downwind, he summoned a grown man's bravery and parted the branches.

The wolf pups, gangly, awkward, with big feet, snapped and squabbled with each other. Their muzzles were stained dark. The mother wolf decisively picked one up by the scruff and deposited it on the other side of the body.

The body.

Sprawled. Motionless. Bloody.

Tral shrieked. The she-wolf's lambent yellow eyes found him. Her powerful haunches gathered and tensed.

She sprang.

**

The tribe was gathered by the time Aruk arrived. He passed through them, wincing at the battering sensation of their minds.

He saw faces blanched ashen with shock, eyes glazed and dull. The hunters held their spears and clubs as if they had no idea what such implements were for. The women huddled. The children clung to their mothers.

The boy, Tral, was quaking like a sapling in a high wind. Garu, First Hunter and leader of the tribe, had an arm around the youngster's shoulders.

Smears of blood, one on each cheekbone and one down the center of his forehead, marked Tral's new status as a man despite his beardless youth. Wolf's blood. It caked the boy's spear, was splashed liberally on his hands and arms.

The wolf, a large and healthy female, lay dead at the base of a tree. Her dead pups were piled nearby.

Aruk stared at the animals, not wanting to look at what he'd been summoned here to see. But Fanri, his sister and eldest of the Old-Mothers, came to his side.

Swallowing hard, bracing himself against the smell of death, Aruk turned his attention to the body.

The wolves had been at it.

But that was not all.

He looked around at the hunters. Hanar, Garu, Noav, young Tral, others. They knew. It beat in their thoughts like a drum. They knew, but they would not say. That was for Aruk to do. To say what the men already knew, and would not voice.

Aruk wanted to shout at them. They were hunters. They had no need of him to tell them. Or did they hope he would say something else? That there might be some answer, some explanation, beyond the one that was so obvious to any man?

The women suspected. He felt it from them, beneath the grief and terror and dismay. But they, too, would not say it.

Their eyes were fixed on the Spirit-Man. Beseeching.

"No wolf did this," he said.

A rippling sigh from the tribe, shoulders slumping, but no looks of surprise.

Death was no stranger to them. They had seen it in countless ways. Hunters trampled beneath hooves, gored by horns, ripped apart by flashing claws and fangs. Women dying in blood and agony trying to give birth. Falls, sickness, the slow death of poison from sting or bite. Those things were all familiar to the tribe.

This, though …

Chala lay with one arm folded awkwardly beneath her torso, the other outflung, fingers nibbled to the bone by the pups. The wolves had torn open her belly to get at the entrails, and chewed the ragged meat of her throat. Her head had been nearly severed.

The life must have spouted from her in a red torrent. Yet little blood soaked the earth. Too little. Not nearly enough.

"It was not done here," Aruk said, hardly aware that he spoke aloud. "She was brought here after her death."

He bent clos

er, lifting away strands of hair. The awful gash gaped wide and straight. No animal claw could have done such a thing.

Grimacing, he reached into the wound. The nearest of the tribe turned away. Aruk tried to close himself to the yammer and gabble of their thoughts. Bad enough that he should constantly have the murmuring of the spirit-voices, let alone all the tribe's.

His fingertips found something hard and sharp. He drew it out and wiped it clean on his wrap before examining it.

A shard of stone. He could have fit it on the nail of his forefinger.

"Flint," he said.

He sat back on his heels and looked at the hunters. When injured prey still struggled and fought, one of them would leap upon the beast and, seizing it by the head, yank a sturdy flint knife hard across the exposed throat.

"Chala was killed by no animal," Aruk said. "She was slain by one of her own kind, her throat cut, and then left here for the scavengers."

Inasa howled and collapsed to her knees, rocking, rending her hair, and shaking off the attempts of the other women to console her.

"You are saying this was done by a man?" Garu said.

"It may have been a woman," Aruk allowed. "But it was one of us."

"No!" Inasha cried. "I will not believe it! One of us? Of this tribe, my tribe? No!"

A fervor and panic of thoughts assaulted Aruk. He pressed the heels of his hands to his temples, eyes squeezed shut. Everyone was speaking at once, shouting at once. The women joined Inasa's loud lamentations, the children were crying, the men roaring to be heard.

It was more than he could bear. His head would split from the force of it, split like a brittle shell. They were in his mind like a storm. Whirling and crashing, a wind and thunder of emotion.

"Stop! No more!"

It was Fanri, her voice shrill and piercing, cutting through the commotion. Aruk felt her tender, gnarled hand on his pain-wracked head.

"No more," she repeated softly into the hush. "You hurt the Spirit-Man with such a noise."

"But to say that one of us did this!" Garu said. "That a hunter of my own tribe killed the daughter of my mate … it cannot be."

"You have seen the work of animals," Aruk said. He opened his eyes, though the patches of daylight through the dapple of leaves felt like many tiny spears jabbing into them. "No beast did this, unless it is a beast that walks on two legs like a man, uses a knife like a man."

The Eye of Mammut

The Eye of Mammut Megan's Wish

Megan's Wish Endless Miles

Endless Miles For The Best

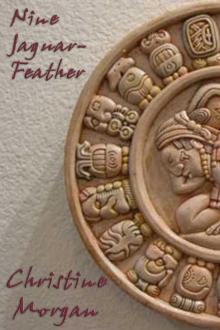

For The Best Nine Jaguar-Feather

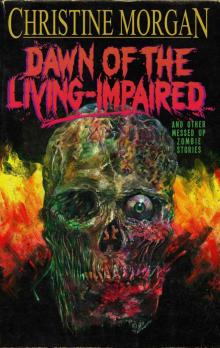

Nine Jaguar-Feather Dawn of the Living-Impaired

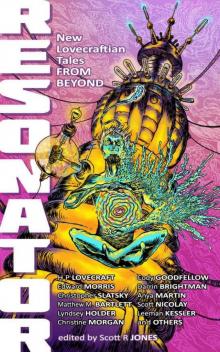

Dawn of the Living-Impaired Resonator: New Lovecraftian Tales From Beyond

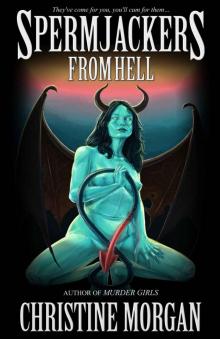

Resonator: New Lovecraftian Tales From Beyond Spermjackers From Hell

Spermjackers From Hell The Raven's Table: Viking Stories

The Raven's Table: Viking Stories The Raven's Table

The Raven's Table